Only Silence Will Never Betray You:

Five Bulgarian Writers

edited and with an introduction by Philip Graham

In the summer of 2017 I was a participant in the Sozopol Literary Seminars in Bulgaria, an annual conference sponsored by the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation. I’d mainly known of Bulgaria through its exquisite and often-otherworldly women’s choral music, which I’d been a fan of since the late 1980s, and so, because my invitation to lead a nonfiction workshop had come a full year early, I was able to do a certain amount of homework in preparation. Whenever I take part in any international conference, I like to search out translations of the literature of the country I’ll be visiting.

I read the novels 18% Gray, by Zachary Karabashliev, Everything Happens As It Does, by Albena Stambolova, Nikolai Grozni’s Wunderkind, and Georgi Gospodinov’s The Physics of Sorrow. As varied as these impressive fictions are, they seemed connected by a combination of humor and soulful melancholy, a literary territory where trouble can perhaps best be endured by bitter laughter and a sometimes-pitiless insight. It seemed a little like a Balkan twist on the not so easily translated Portuguese concept of “saudade,” a single word that mingles sorrow and longing, tenderness and pain.

I also delved into the country’s history and culture, beginning with Kapka Kassabova’s memoir, Street Without A Name, and a couple of travel books, including Patrick Leigh Fermor’s travel memoir from the 1930s, The Broken Road. What I learned gave context to the fiction I’d been reading. A good portion of modern Bulgaria was once the site of the ancient culture of Thrace, lying north of and contemporaneous with ancient Greece. Famous Thracians include Democritus, who came up with the idea of the atom, and Spartacus, whose slave revolt almost brought down the Roman Empire. Plovdiv, Bulgaria’s second largest city, was named Philippopolis after it was conquered by Philip II of Macedon (father of Alexander the Great) in the fourth century, BC. Constantine the Great (founder of the Byzantine Empire) was born not far from what is now Bulgaria’s capital city, Sofia (then known as Serdika), and he declared that it was his favorite city. The Cyrillic alphabet was first developed in Bulgaria, not Russia. The basis for almost all commercial yogurt, since the early twentieth century, is the bacterial strain Bacillus bulgaricus.

But my deepest take-away was how difficult Bulgaria’s history has been for the past 500 years. Becoming an administrative province of the Ottoman Empire even before the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Bulgaria didn’t receive its independence until the late nineteenth century. The twentieth offered little improvement, with two disastrous alliances with Germany in the First and Second Worlds Wars, then nearly half a century of imposed communist rule, as a member of the Eastern European Soviet bloc. Today, Bulgaria still struggles to confront the ghosts of the distant and recent past, and the uncertainties of this unfinished cultural business is a reason, I think, that contemporary Bulgarian literature contains so much energy and excitement. Silence may never betray you (to paraphrase the title of one of Marin Bodakov’s poems included in this anthology), but writers must always speak. That’s why others, locked in their silence, listen to them. And why writers are sometimes shunned, imprisoned or killed.

The Sozopol Seminars, which took place in Sofia and the Black Sea resort town of Sozopol, turned out to be a vibrant cultural and literary exchange. Bulgarian writers, including Nikolai Grozni, Georgi Gospodinov (whose novels I’d recently read and admired), and poet Marin Bodakov, met with visiting writers like Benjamin Moser, Josip Novakovich, Philip Gourevitch, Ladette Randolph, and Elif Batuman, with novelist Elizabeth Kostova presiding over it all. And the five nonfiction fellows I had the privilege to work with were a stunningly talented bunch. When it was all over, I decided that I wanted to bring back a little of that Bulgarian literary goodness to Ninth Letter, and so here is our mini-anthology titled “Only Silence Will Never Betray You: Five Bulgarian Writers.” While it contains one emerging as well as four well established writers that I met at the conference, this anthology is a mere hint of the country’s wide range of talent.

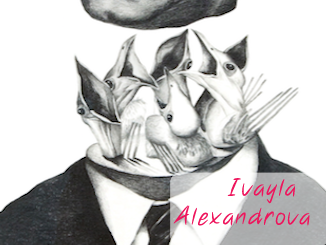

The except here from Ardent Red, Ivayla Alexandrova’s “documentary novel,” directly confronts Bulgaria’s conflicted recent past, specifically the early years after the imposition of communism, when government purges imprisoned or killed thousands of people, including many of the country’s prominent artists. Alexandrova’s focus on the harrowing details of the arrest and death of the writer and satirist Rayko Alexiev is just one poignant example of all the other victims of those purges.

In writing this introduction, I’ve noticed that two of the writers here offer work that takes place outside the borders of Bulgaria—Brazil and France, while a third writer’s short story takes place on a train. Perhaps because of nearly a half-century of travel restrictions on Bulgarians by the communist government, out of fear of mass emigration to the West (thousands were killed in their attempts to escape), Bulgarians now revel in the civil right of simply leaving, or moving about unrestricted.

“Carnival Actually Happens on the Streets,” by the emerging writer Bistra Andreeva, a journalist and translator (and one of many fine younger Bulgarian writers at the Sozopol conference), is an essay that casts a Bulgarian gaze at a very different culture. Andreeva takes us to the side streets of Rio during the Brazilian season of carnival, where the celebrations of local neighborhoods more than rival the energy of the spectacular official parades seen on television.

“Freaks” and “The Death of the Village Postman,” two fever dream short stories from Nikolai Grozni’s collection, Claustrophobias, take place in France, but really, their marvelous back-and-forth weavings are lodged in the mind of the Bulgarian narrator, a sort of not-so-innocent abroad.

“Daughter,” an eerie and unsettling short story by Georgi Gospodinov, mainly takes place on a train heading toward the city of Sofia, and tells the tale of an encounter with a man who is accompanying his doll for perhaps one last ride.

Finally, we come to a selection of poems by Marin Bodakov, poems that combine brevity with powerful, restrained emotion, poems whose very brevity invites rereading and further revelations.

Since traveling to Bulgaria, I have continued exploring that country’s literature: Deyan Enev’s Circus Bulgaria, Georgi Tenev’s Party Headquarters, Ivailo Petrov’s Wolf Hunt, A Short Tale of Shame, by Angel Igov, and Kapka Kassabova’s travel memoir, Borders. There has been a surge of translations of contemporary Bulgarian literature in recent years (much of it sponsored by the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation), and we here at Ninth Letter hope that readers will be inspired by this anthology feature to do their own exploring.

My thanks to Milena Devela, Simona Ilieva, Jeremiah Chamberlin and Elizabeth Kostova for organizing such a splendid literary conference, and to translator Boris Deliradev, Elena Alexieva, and Ana Blagova.