In 2020, Ninth Letter initiated a series we called “A Book You May Have Missed,” in order to call attention to worthy books published during the pandemic year that may have been lost in the shuffle of viruses and quarantines, protests and counterprotests, election fears and the slow dread of an impending insurrection.

The first two books in our series celebrated Michele Morano’s Like Love and Sarah Minor’s Bright Archive, and now, as the coronavirus pandemic grinds through its second year with no clear end in sight, many more books have accumulated that deserve a recommendation—and, of course, more grateful readers. Every book featured below, though published in our plague years of either 2020 or 2021, was written before the world changed, and yet they each uncannily contain lessons for us about the world in which we now find ourselves. Or maybe that quality isn’t so uncanny: the best books embody their time and yet transcend that time.

Of course many other books published during these past two years are necessary reads, including Danielle Evans’ razor-sharp The Office of Historical Corrections; the landmark anthology of African-American history, Four Hundred Souls, edited by Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain; and Kazuo Ishiguro’s meditation on a future, ever more constricted class system and the limitations of the human heart, Klara and the Sun. To name only a few. Yet even if you haven’t yet read those books, you’ve probably heard of them. The following recommendations in this Ninth Letter feature are for books that, through no fault of their own, fell below the radar during the pandemic, yet each adds a no less important voice to our collective literary conversation.

—Philip Graham

Robin Hemley, Borderline Citizen

Hemley’s essay collection launched on March 1, 2020, just ten days before the WHO declared the coronavirus outbreak a global pandemic. A crisis caused by a deadly virus that easily crosses borders is perhaps the worst circumstance for a “polygamist of place” to release a book of travel essays. Nineteen months later, travel restrictions hold fast around the globe, yet Borderline Citizen remains an ideal book for us unwilling sticks-in-the-mud to read, because Hemley doesn’t simply travel to other countries; instead, his travel focuses on the complex and contradictory people he finds there. National borders may be powerful fictions, but the individuals residing within those fictions are real, and Hemley brings them to life through his sympathetic curiosity. Reading these wide-ranging and vividly attentive essays can shape us into better travelers for our eventual After-times journeys.

Scholastique Mukasonga, Igifu

The title story of Rwandan author Mukasonga’s latest collection, Igifu, translates as “hunger,” and depicts its daily grinding invisible presence among the poor. But her story “Fear” tracks most closely our experiences during the pandemic. The narrator of “Fear,” a young Tutsi girl, has learned to be constantly on the alert for another outbreak of genocidal violence at the hands of the Hutu majority in Rwanda. “Death is lurking everywhere, waiting for its chance,” the narrator’s mother warns her. “You have to admire the fly: it can see on every side at once. It is good to be afraid. Fear keeps us awake, our guardian angel is fear.”

Though this training in the necessary benefits of a finely-honed fear takes place a world away, in East Africa, it feels all too familiar to the invisible paths of fear African-Americans have to navigate every day in the US, where the slightest wrong turn can suddenly morph into another George Floyd tragedy. And now that essential alertness is a skill everyone has had to learn, in the face of the hovering unpredictability of the coronavirus.

Mary Cappello, Lecture

In 2018, Ninth Letter published Mary Cappello’s essay “A Lecture on the Lecture.” Since then, Cappello expanded her essay into book-length form, now simply titled, Lecture.

Cappello takes a deep look at this ubiquitous oral art form and reveals it to be a strangely neglected genre of literature. “I am convinced,” she writes, “that I learned how to read and write by listening to the Americanist scholar Martin Pops lecture.” But this marvelous book is not so much about praising the lecture as it is about reimagining it: “What if the lecture began with questions from the audience and moved out from there? To dispense with the hierarchy of introductions (that no one listens to), words of thanks (ditto), easing in and inviting you (you continue not to listen), and go directly to the Q and A. Start there. But instead of your Q to my A, you give me an A for which I supply an A to which you supply a Q with A to which I supply an AQQA and so on until a tempo of thought emerges.”

Written before but published during a time of remote Zoom classes, Cappello’s Lecture offers a bracing reminder of what the face-to-face classroom experience once was. While the return to the classroom is now underway—rife with disputes over masking and fear of the unvaccinated—the vision of Cappello’s book offers not a return to a former normalcy, but a reimagining of the drama of learning, for both student and teacher.

Patrick Madden, Disparates

This collection of essays was such a gift during the pandemic—these essays aim to be fun, even silly. Madden’s usual graceful seriousness is leavened here with extra does of wit, even in an account of all the car accidents he’s survived.

To mix up the proceedings, Madden—one of our finest essayists—adds occasional puzzles and photos, haikus and pretzeled proverbs. He even invites other writers to join or add to some of his essays, breaking down the usual writerly isolation, as if anticipating the Coming of Zoom to the enforced isolation of our lives. And he remains endlessly charming. At the beginning of the short essay “Poetry,” his seven-year-old daughter one day mentions in passing that “I’ve never seen the top of my head,” which leads Madden to a quick meditation on heads and perspective and how to recognize the poetry of a moment when it arrives, which this insight effectively sums up: “Of course, I’ve seen the top of her head since the day she was born, and even now, because I am nearly twice her height, when we go walking, I see the top of her head when I glance down. It is a father’s perspective. Or a god’s.”

Dinty W. Moore, To Hell with It

2021 marked our second year of the pandemic and the 700th anniversary of the death of Dante, author of the Divine Comedy. While a spate of articles and books have appeared praising Dante’s poetic genius, Moore has another take: that Dante’s horrifying and personal imagery of hell (because very little of it was dependent on biblical sources) is responsible for centuries of fearful minds and more than mere psychological misery. In Moore’s prologue, he writes, “The concepts of Hell and sin—whether we actively accept them or not—have been tightly woven into our core cultural tapestry, fashioning our churches and religions—obviously—but also our legal structure, our penal systems, our views on poverty and class, our classic and contemporary literature, and much of our interpretation of history.”

Moore illustrates this large assertion with close accounts of his Catholic upbringing and the lives of his parents and grandparents—portraits suffused with his trademark empathy and self-deprecating wit. Yet I kept returning to the notion that a single poet’s inferno of a fantasy life could wreak so much damage, and I thought of the social media fantasies of today, how the imaginations of QAnon conspiracists and anti-vaccination paranoids have shaped too much of our current political dilemmas and extended the spread of a deadly virus.

Yuri Rytkheu, When the Whales Leave

This novel by Chukchi (indigenous Siberian) writer Yuri Rytkheu celebrates the mythic time when a close relationship between humans and the natural world existed, and laments the eventual fracturing of that relationship. The novel tells the story of Nau, the mother of humankind, and Reu, her husband who was originally a whale, and the generations that followed. Each successive generation doubts a little more of Nau’s teachings about the past and what she calls “Great Love” (a commitment to common good rather than selfish individual advancement). Each generation, to their deep detriment, forgets a little further the need for balance with nature. Rytkheu’s novel is a finger pointing to a fearsome future, one that now seems on the verge of arriving: I read this book while record-breaking wildfires and drought ravaged the far west of the US, and temperatures exceeding 100 degrees were recorded as far north as Siberia.

YOSS, Red Dust

In Red Dust, the Cuban science-fiction writer José Miguel Sánchez Gómez—who writes pseudonymously as YOSS—presents one of his most engaging creations: Raymond, a well-meaning robot detective in the distant future who tries his best to understand the confounding ways of humans.

Near the end of this funny, exciting adventure, Raymond watches Vasily, a law-enforcement ally, engage in a crucial battle of mentally-generated forcefields against the dangerous criminal Makrow, and he discovers the weakness of color symbolism: “It looked to me like Vasily’s field was navy blue, almost black, while Makrow’s was pinkish white—which for some reason I found almost shocking. Wasn’t the purest color supposed to be for the good guy? It’s hard to put any credit in archetypes after a surprise like that.”

The words “dark” or “darkness” have become embedded in the English language as metaphors for whatever is disturbing or bad. Yet Raymond’s shock is worth contemplating, especially with the example of our own recent battles, when in November of 2020 and then in Georgia in January of 2021, people of color voted in droves to help save the country from electoral fates worse than death.

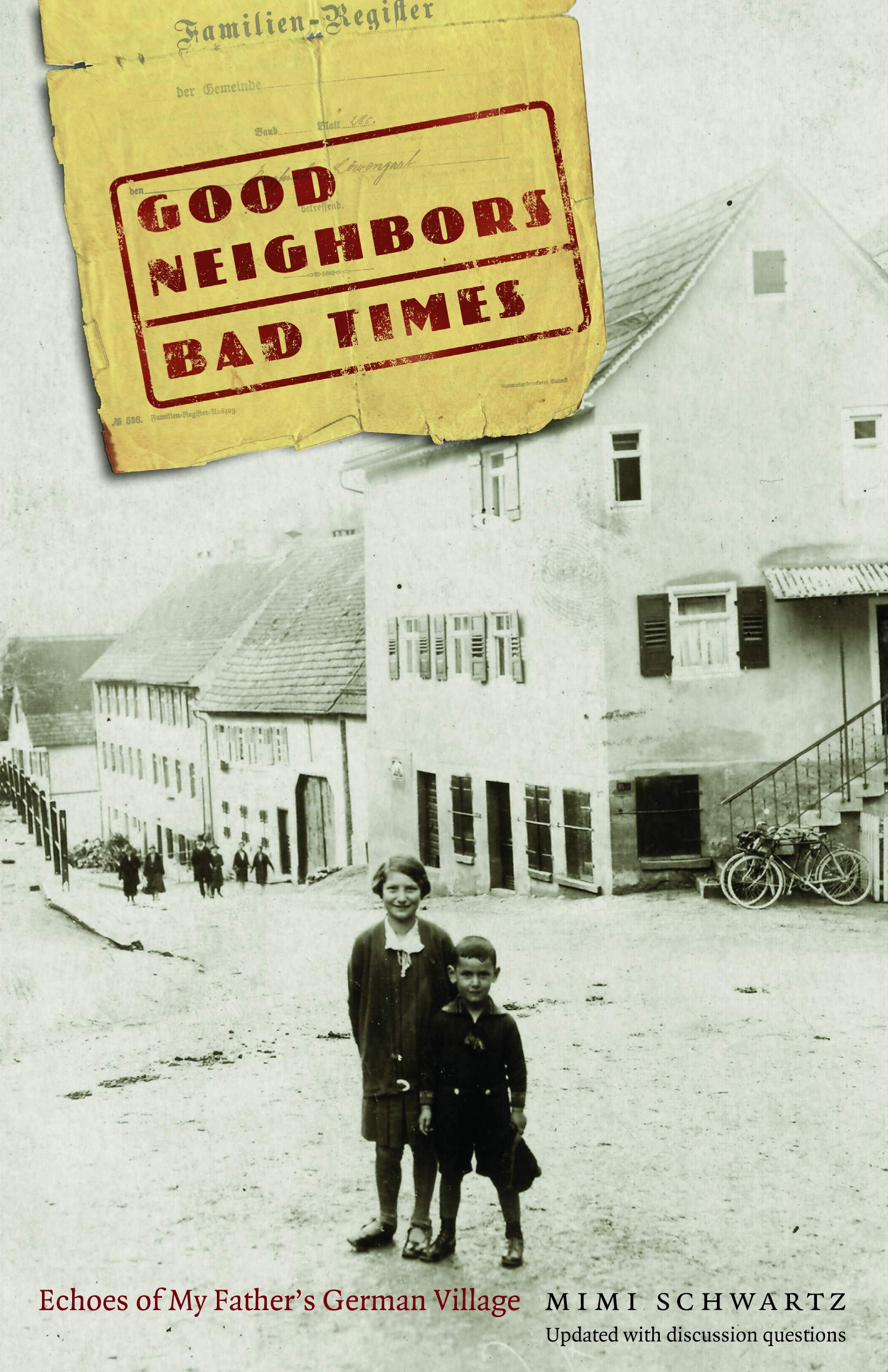

Mimi Schwartz, Good Neighbors, Bad Times Revisited

Authors revise relentlessly. Usually that process ends when a book is finally published. That’s certainly what Mimi Schwartz must have expected after the publication of Good Neighbors, Bad Times, her recreation of life in the small village of Rexingen, Germany, where generations of her family had lived before escaping to the US in the 1930s. Villagers liked to assert that “we all got along,” but trust between Jews and Christians broke down after Kristallnacht, even though the police saved two Torahs from the burning Rexingen synagogue.

Years after her book’s publication, Schwartz received in the mail the manuscript of a memoir written by Max Sayer, who grew up Catholic in the village in the 1930s and 40s. With Sayer’s permission, Schwartz has woven his account throughout her new edition of Good Neighbors, Bad Times, creating an even richer portrait of the subtle ways a village “can come apart when a nation turns to hate,” a portrait that feels unnervingly recognizable.

Ben Okri, Prayer for the Living

Ben Okri won the 1991 Booker Prize for The Famished Road, a novel told in the voice of a spirit child born into a human family in Nigeria. It’s one of my favorite novels, though I haven’t kept up with Okri’s most recent work. I only noticed his new story collection, Prayer for the Living, while passing a bookstore table six months after the book’s early 2021 release.

The stories are set in locales around the world, and range in style from realism to fantasy, from grim to playful, yet the stories are ultimately held together by Okri’s inquisitive, probing mind. My favorite story is “Don Ki-Otah and the Ambiguity of Reading.” In this story, an African incarnation of Don Quixote enters a printshop in contemporary Lagos and conducts a discussion about books and reading. Don Ki-Otah has a lot to say, and this riff is just one example:

“I don’t read slowly. And I have long ago left reading fast to those who will continuously misunderstand everything around them. I read now the way the dead read. I read with the soles of my feet. I read with my beard. I read with the secret ventricles of my heart. I read with all my sufferings, joys, intuitions, all my love, all the beatings I have received, all the injustices I have endured. I read with all the magic that seeps through the cracks in the air.”

Reading, during these paired pandemic years, has felt more intense to me, and the stakes more important. As Okri makes clear in the above passage, reading is not mere relaxation, and books offer more than an opportunity to fill a hole in the day. The best books ask for open-hearted attentiveness, and in turn give back to a reader much more. The ongoing threat of invisible viruses in the air has perhaps kept us more alert than usual, perhaps more willing to receive the gifts of a book we hold in hand. We at Ninth Letter would like to suggest that any of the books we’ve featured here, these books you may have missed, will amply reward your willing gaze.